© 2004-2021 Thomas Jäkel

Wagler's Viper and the

Snake Temple at Sungei

Kluang on Penang Island,

Malaysia

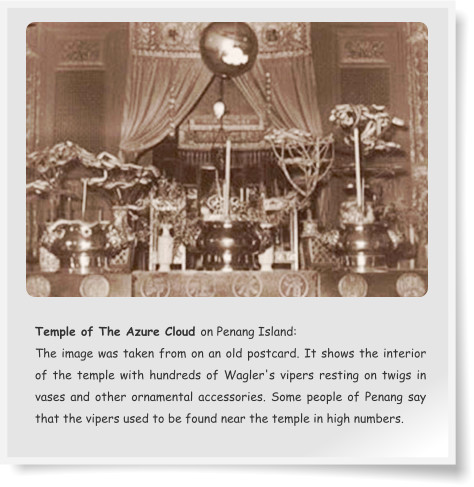

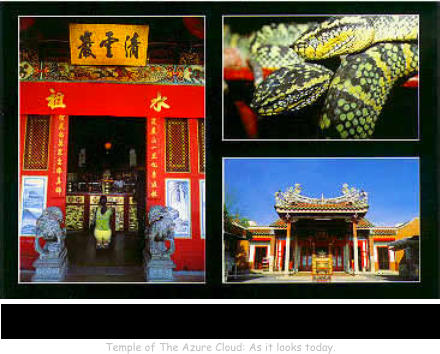

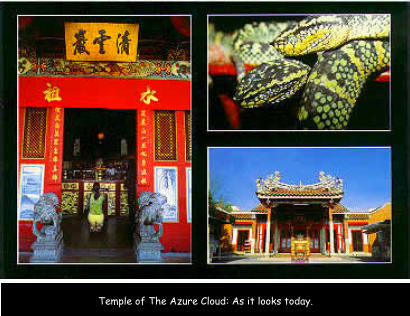

The Temple of the Azure Cloud, commonly known as the Snake Temple, is a world-famous destination for travelers that visit Penang island in Malaysia. Its fame is invariably connected with this snake species. The image on the right was displayed on an old postcard from Penang. Unfortunately, this "golden age" of high abundance of the temple viper on Penang has passed. A few animals can still be seen inside the building, yet, they are often not in a good shape (see our "health problems" section). I have observed that T. wagleri is collected by locals to regularly restock the population in the temple. Contrary to popular belief, the snakes do not feed on the eggs and other food items donated by visitors. Therefore, most of the animals probably starve to death. This is aggravated by the fact that fangs are removed from those snakes that serve for posing with visitors taking photographs.Taxonomic Position

Common name: Wagler's Palm Viper, Wagler's Temple Pit Viper Distribution: Brunei Darussalam; Indonesia (Sumatra, Mentawi, Nias, Riau Archipelago, Billiton, Bangka, Natuna, Borneo/Kalimantan, Karimata, Buton, Sulawesi), Malaysia (Malaysian peninsular and East Malaysia); Philippine Islands (including Sulu Archipelago, Panay); Singapore Southern Thailand (northern range up to Puket and Khao Lak) The genus Tropidolaemus (Family: Viperidae; Subfamily: Crotalinae), first coined by Wagler in 1830, represents a clade of primitive pit vipers of the Old World. It was subsequently merged into the Asiatic lance-headed pit viper complex (Trimeresurus sensu lato) for a long period of time. Morphologically the genus Tropidolaemus appears rather different from the rest of Trimeresurus species, in which Tropidolaemus is characterized by several unique features including the absence of a nasal pore, strongly gular keels, head covered with distinctly keeled small scales, and a hemipenis type that is closer to Asian basal pit vipers like Deinagkistrodon acutus, Calloselasma rhodosotma and Hypnale hypnale. The genus Tropidolaemus was finally resurrected as a distinct genus, without close relationship to the genera once contained within the Trimeresurus complex (Creer, Malhotra & Thorpe 2003). A major taxonomic revision of the genus Tropidolaemus has been published (Vogel et al. 2007), but is still not concluded. The paper has been published in the journal 'Zootaxa', which also describes new species of Tropidolaemus. Currently recognized species of the genus Tropidolaemus: Tropidolaemus huttoni (SMITH, 1949) Tropidolaemus laticinctus (KUCH, GUMPRECHT & MELAUN, 2007) Tropidolaemus philippensis (GRAY, 1842) Tropidolaemus subannulatus (GRAY, 1842) Tropidolaemus wagleri (BOIE, 1827)Phylogenetic Data

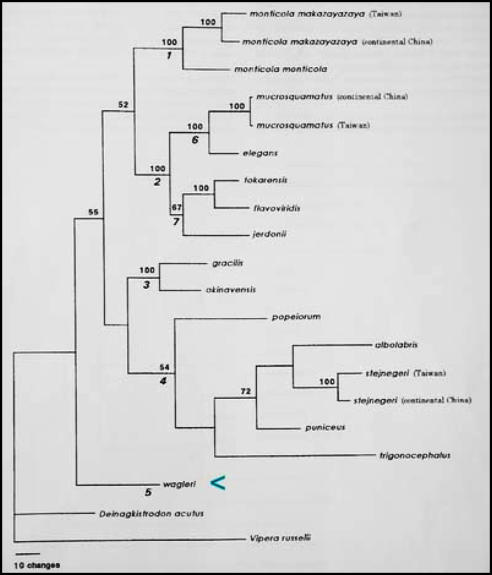

Two early genetic analyses of members of the Trimeresurus group and related genera (Tu et al. 2000; Giannasi et al. 2001) supported the distinction between Tropidolaemus and Trimeresurus (see tree below: position of T. wagleri is indicated by blue arrowhead), which has been confirmed by later studies (Creer, Malhotra & Thorpe 2003). The phylogenetic tree below is based on sequence data for the mitochondrial 12s rRNA gene (Tu et al. 2000).Population Systematics

Genetic analyses of mitochondrial DNA and morphological data suggested that there are at least two different groups of animals. The populations from Sumatra and Western Malaysia are distinct from those from Borneo and Sulawesi. This suggested that there are at least two species of Tropidolaemus, whereby the the name T. wagleri should be restricted to Sumatran/western Malaysian populations (Ulrich Kuch & Nicolas Vidal, Congress Evolution 2002). Since then, populations from Borneo, Sulawesi and Philippines have been designated as T. subannulatus (Vogel et al. 2007). New species have been described from the Philippines (T. philippinensis) and from northern Sulawesi (T. laticinctus, Kuch, Gumprecht & Melaun 2007).References

Boie (1827) Isis van Oken, Jena, 20: 508-566. Boulenger (1894) Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. (6) 14: 81-90 Brattstom (1964) Trans. San Diego Soc. Nat. Hist. 13: 185-268 Cox et al.(1998) Guide Snakes Rept. Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Cranbrook & Edwards (1994) A Tropical Rainforest, Roy. Geo. Soc. & Sun Tree Publ. Creer, Malhotra & Thorpe (2003) Mol Biol Evol 20, 1240–1251. David & Vogel (1996) The Snakes of Sumatra. de Rooij (1917) The Rept. Indo-Australian Archipelago. Il. Ophidia. Duméril & Bibron (1854) Erpétologie générale Vol. 7/2. Ferner et al. (2001) Asiatic Herpetological Research. 9: 34-70 Giannasi et. al. (2001) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 19: 57-66. Gopalakrishnakone & Chou, eds. (1990) Snakes of Medical Importance, National University of Singapore Gray (1842) Zoological Miscellany 2, 47–51. Grossmann et al. (2001) Sauria 23 (1): 25-40 Grossmann et al. (2001) Sauria 23 (3): 21-34 Kuch, Gumprecht & Melaun (2007) Zootaxa 1446: 1–20. Kuch & Vidal (2002) Congress Evolution Leviton (1964) Phil. J. Sci. 93: 251-276 Manthey & Grossmann (1997) Amph. & Rep. Suedostasiens McDiarmid et al. (1999) Snake species of the world, v.1. Parkinson (1999) Copeia 1999 (3): 576-586 Pauwels et al. (2000) Dumerilia 4 (2): 123-154 Stuebing & Inger (1999) A field guide to snakes Borneo. Tu et al. (2000) Zoological Science 17: 1147-1157 Vogel (2006) Venomous snakes of Asia, Chimaira Vogel et al. (2007) Zootaxa 1644: 1-40 Wagler (1830) Natürliches System der Amphibien; J. G. Cotta Buchhandlung.

- Home

- Wagler's Viper Site (WVS)

- General Husbandry - WVS

- Breeding - WVS

- Health Problems - WVS

- Taxonomy and Phylogenetics - WVS

- Biology - WVS

- Geographic Variability - WVS

- How Females Change - WVS

- Venom - WVS

- Image Map - WVS

- Special: T. laticinctus - WVS

- Special: North Sumatra - WVS

- Special: Video on Mating - WVS

- Special: North Sulawesi - VVS

- Biological Rodent Control - BRC

- Rodent Management Laos - BRC

- Gallery

- Contact