© 2004-2021 Thomas Jäkel

Biology

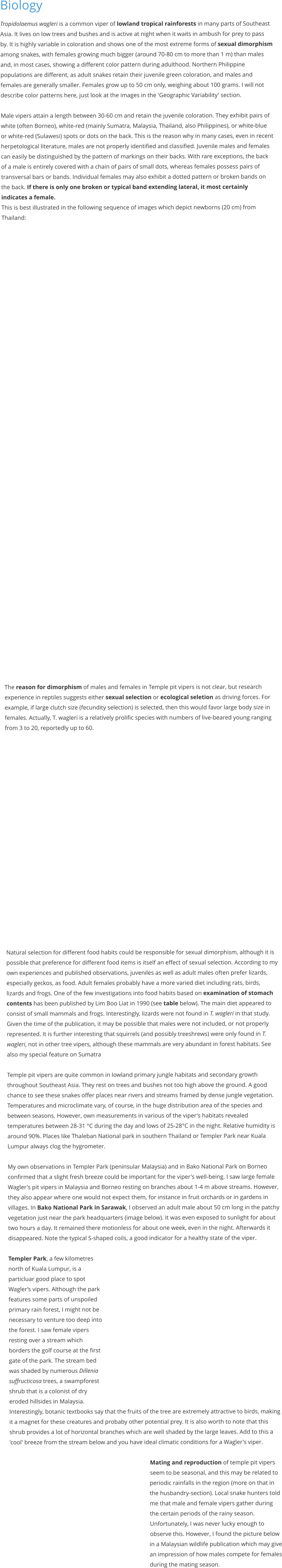

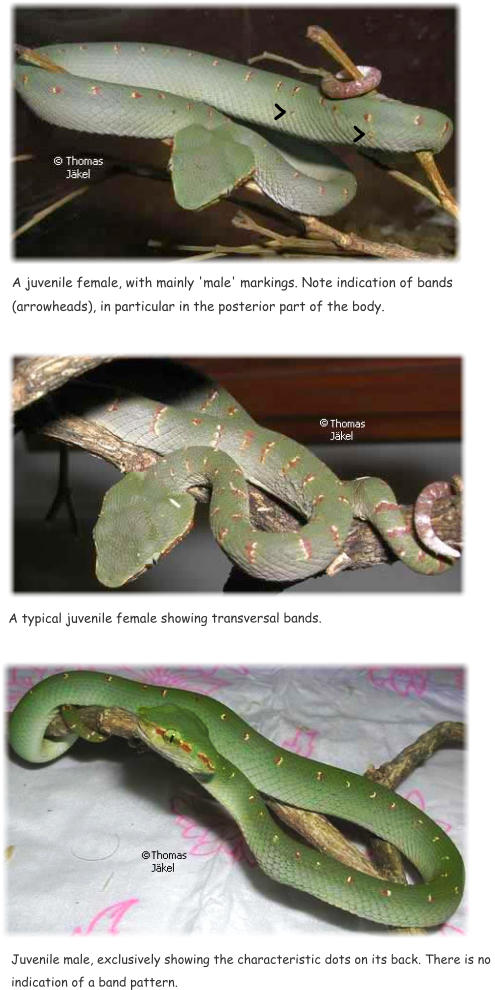

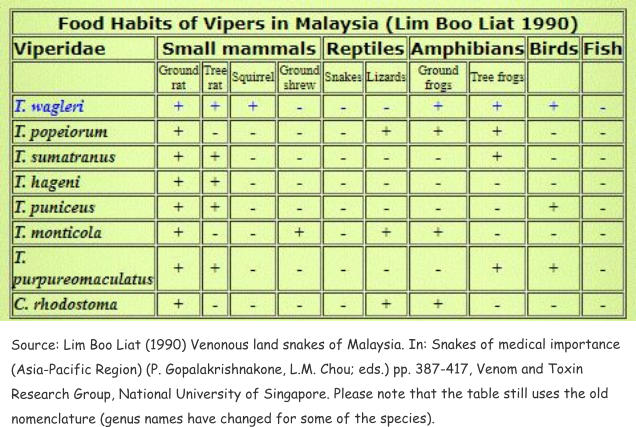

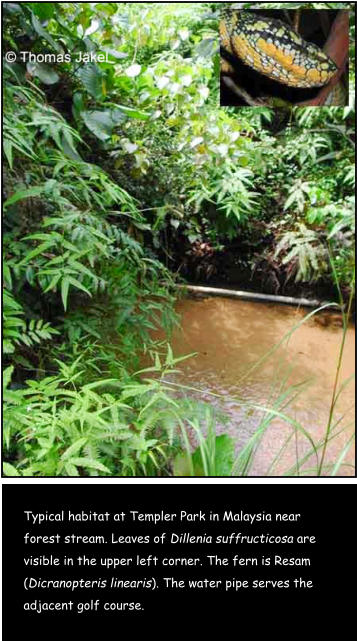

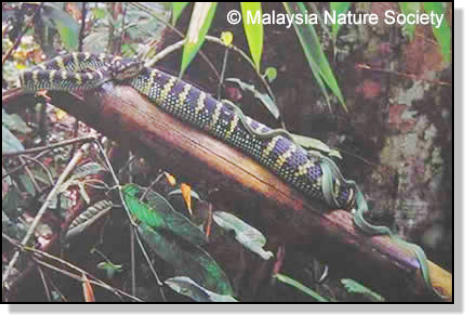

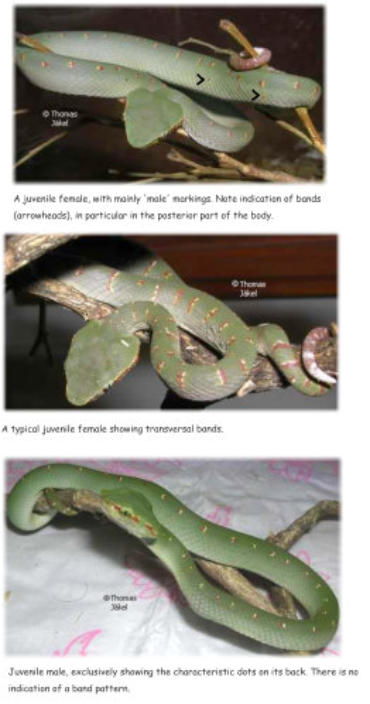

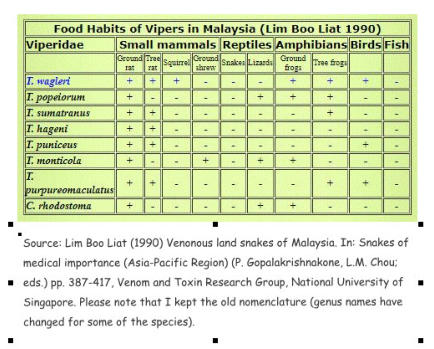

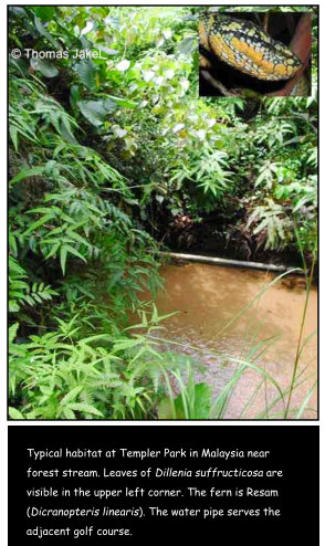

Tropidolaemus wagleri is a common viper of lowland tropical rainforests in many parts of Southeast Asia. It lives on low trees and bushes and is active at night when it waits in ambush for prey to pass by. It is highly variable in coloration and shows one of the most extreme forms of sexual dimorphism among snakes, with females growing much bigger (around 70-80 cm to more than 1 m) than males and, in most cases, showing a different color pattern during adulthood. Northern Philippine populations are different, as adult snakes retain their juvenile green coloration, and males and females are generally smaller. Females grow up to 50 cm only, weighing about 100 grams. I will not describe color patterns here, just look at the images in the 'Geographic Variability' section. Male vipers attain a length between 30-60 cm and retain the juvenile coloration. They exhibit pairs of white (often Borneo), white-red (mainly Sumatra, Malaysia, Thailand, also Philippines), or white-blue or white-red (Sulawesi) spots or dots on the back. This is the reason why in many cases, even in recent herpetological literature, males are not properly identified and classified. Juvenile males and females can easily be distinguished by the pattern of markings on their backs. With rare exceptions, the back of a male is entirely covered with a chain of pairs of small dots, whereas females possess pairs of transversal bars or bands. Individual females may also exhibit a dotted pattern or broken bands on the back. If there is only one broken or typical band extending lateral, it most certainly indicates a female. This is best illustrated in the following sequence of images which depict newborns (20 cm) from Thailand: The reason for dimorphism of males and females in Temple pit vipers is not clear, but research experience in reptiles suggests either sexual selection or ecological seletion as driving forces. For example, if large clutch size (fecundity selection) is selected, then this would favor large body size in females. Actually, T. wagleri is a relatively prolific species with numbers of live- beared young ranging from 3 to 20, reportedly up to 60. Natural selection for different food habits could be responsible for sexual dimorphism, although it is possible that preference for different food items is itself an effect of sexual selection. According to my own experiences and published observations, juveniles as well as adult males often prefer lizards, especially geckos, as food. Adult females probably have a more varied diet including rats, birds, lizards and frogs. One of the few investigations into food habits based on examination of stomach contents has been published by Lim Boo Liat in 1990 (see table below). The main diet appeared to consist of small mammals and frogs. Interestingly, lizards were not found in T. wagleri in that study. Given the time of the publication, it may be possible that males were not included, or not properly represented. It is further interesting that squirrels (and possibly treeshrews) were only found in T. wagleri, not in other tree vipers, although these mammals are very abundant in forest habitats. See also my special feature on Sumatra Temple pit vipers are quite common in lowland primary jungle habitats and secondary growth throughout Southeast Asia. They rest on trees and bushes not too high above the ground. A good chance to see these snakes offer places near rivers and streams framed by dense jungle vegetation. Temperatures and microclimate vary, of course, in the huge distribution area of the species and between seasons. However, own measurements in various of the viper's habitats revealed temperatures between 28-31 °C during the day and lows of 25-28°C in the night. Relative humidity is around 90%. Places like Thaleban National park in southern Thailand or Templer Park near Kuala Lumpur always clog the hygrometer. My own observations in Templer Park (peninsular Malaysia) and in Bako National Park on Borneo confirmed that a slight fresh breeze could be important for the viper's well-being. I saw large female Wagler's pit vipers in Malaysia and Borneo resting on branches about 1-4 m above streams. However, they also appear where one would not expect them, for instance in fruit orchards or in gardens in villages. In Bako National Park in Sarawak, I observed an adult male about 50 cm long in the patchy vegetation just near the park headquarters (image below). It was even exposed to sunlight for about two hours a day. It remained there motionless for about one week, even in the night. Afterwards it disappeared. Note the typical S-shaped coils, a good indicator for a healthy state of the viper. Templer Park, a few kilometres north of Kuala Lumpur, is a particluar good place to spot Wagler’s vipers. Although the park features some parts of unspoiled primary rain forest, I might not be necessary to venture too deep into the forest. I saw female vipers resting over a stream which borders the golf course at the first gate of the park. The stream bed was shaded by numerous Dillenia suffructicosa trees, a swampforest shrub that is a colonist of dry eroded hillsides in Malaysia. Interestingly, botanic textbooks say that the fruits of the tree are extremely attractive to birds, making it a magnet for these creatures and probaby other potential prey. It is also worth to note that this shrub provides a lot of horizontal branches which are well shaded by the large leaves. Add to this a 'cool' breeze from the stream below and you have ideal climatic conditions for a Wagler's viper. Mating and reproduction of temple pit vipers seem to be seasonal, and this may be related to periodic rainfalls in the region (more on that in the husbandry-section). Local snake hunters told me that male and female vipers gather during the certain periods of the rainy season. Unfortunately, I was never lucky enough to observe this. However, I found the picture below in a Malaysian wildlife publication which may give an impression of how males compete for females during the mating season.

- Home

- Wagler's Viper Site (WVS)

- General Husbandry - WVS

- Breeding - WVS

- Health Problems - WVS

- Taxonomy and Phylogenetics - WVS

- Biology - WVS

- Geographic Variability - WVS

- How Females Change - WVS

- Venom - WVS

- Image Map - WVS

- Special: T. laticinctus - WVS

- Special: North Sumatra - WVS

- Special: Video on Mating - WVS

- Special: North Sulawesi - VVS

- Biological Rodent Control - BRC

- Rodent Management Laos - BRC

- Gallery

- Contact